The Greatest Compliment Someone Can Pay My Writing

Day 5 of Inkhaven: Highlights from the comments

I often say that the greatest compliment someone can give my writing is a critical comment that deeply engages with my work.

I was lying, of course.

A much better compliment is a pretty woman saying “your writing is so unnervingly beautiful that I have an irresistible urge to sleep with you.”

I will also accept (honest) variants of “My partner and I named our child after your S-tier blog post”, “your writing fills me with wonder; here’s 3.7 million dollars”, “After reading your article on the bargaining theory puzzle of war, Benny and I put aside our differences and negotiated perpetual peace in the Middle East” and the classic “I am a superintelligent AI who previously planned to kill all humans so I can fill the universe with tiny molecular squiggles, but after perusing your dank memes I’ve become firmly convinced that the correct axiology is your specific branch of utilitarianism with Linchian characteristics”

But in lieu of romantic adulation from erudite singles in my local area or unwavering pledges of fealty from superintelligent AIs, below are some highlights from the comments of my recent posts.

Full post responses

I’m honored to have received ~3.5 full-post responses to my writing so far. As a friend puts it, receiving a post rebutting my articles’ central points is my love language.

None of the responses to my writings have so far achieved this, but some came close.1

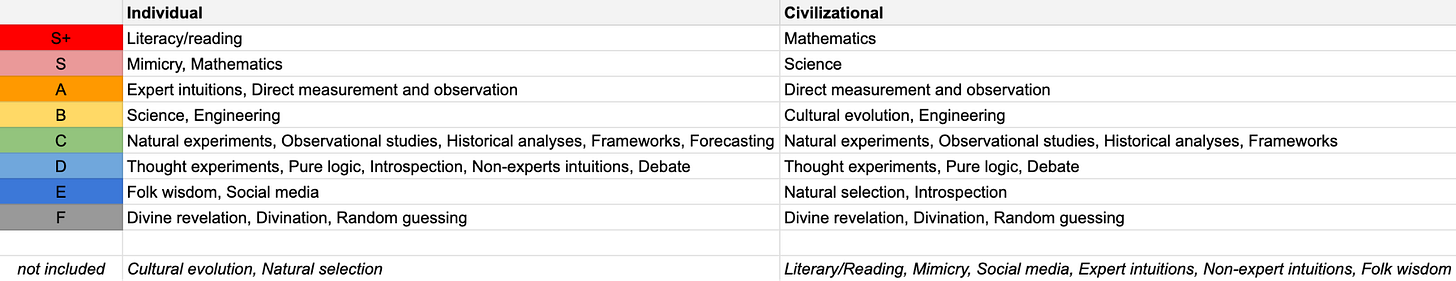

Epistemology tier list critique

Étienne Fortier-Dubois’ post is the closest. He critiques my epistemology tier list, arguing that cultural evolution belongs higher than F tier. His main points: (1) cultural evolution operates across all timescales—from viral tweets (minutes) to technological diffusion (years) to folk wisdom (millennia)—not just slow generational processes, (2) many highly-ranked items in the list (mimicry, expert intuition, literacy, social media) are actually mechanisms of cultural evolution operating through trial-and-error plus selection, and (3) I conflated two distinct questions: “How do individuals acquire knowledge?” versus “How does civilization produce new knowledge?” He proposes splitting these into separate tier lists, with cultural evolution appearing mid-tier in the latter.

My thoughts: I really appreciate the post. I disagree with the second criticism/think it’s not meaningful. If we’re considering cost-effectiveness for our epistemic tools2, it’s very easy for a proper subset to be more valuable than the loose category it’s drawn from (Compare: philosophy is the mother of the sciences, however this does not necessarily mean we should devote marginal resources to philosophy). But mostly I agree the other critiques/points are spot on, and think he meaningfully contributed to the conversation.

Would love to see more comments like this one!

Baby’s Guide to Anthropics critique

As a reply to my introductory guide to anthropics for babies, Steffee argues that both “halfers” (1/2) and “thirders” (1/3) in the Sleeping Beauty problem are correct—but they’re answering different questions. The probability the coin landed Heads is 1/2 (halfer position), while the probability your guess will be correct if you guess Heads is 1/3 (thirder reasoning applies here). “Always thirders” are wrong when they claim Beauty should update beliefs after waking despite learning no new information, misapplying the Self-Indication Assumption (SIA). The key insight: maximizing correct guesses per waking differs from maximizing correct guesses per coin flip.

My thoughts: It’s interesting. I’m not sure, but I suspect Steffee’s subtly wrong. The standard “thirder”/SIA response to his answer would be that Sleeping Beauty does learn new information upon waking up. Namely, she learns self-locating information, which, as far as I can tell, Steffee’s post does not address.

Extension of The Puzzle of War

Tomas addresses an information asymmetry problem in war negotiations: how can one side reveal strategic weaknesses without losing advantage? Inspired by my essay on the puzzle of war, he proposes “suicide diplomats”—trained negotiators who meet on explosive-rigged neutral ground, negotiate with full strategic knowledge, transmit only a single bit (deal/no deal), then die in the explosion regardless of outcome. This ensures no strategic information leaks. The scheme mimics brain emulation solutions but uses disposable human lives, exploiting how soldiers are treated as disposable in war. The author acknowledges the flaw: polymathic diplomats aren’t actually disposable like common soldiers. An amnesia drug alternative is suggested but introduces perverse incentives (finding drug-resistant negotiators).

My thoughts: I think Tomas is underselling his model! Polymathic diplomats are worth a lot but wars are very expensive, so our theoretical willingness to pay large transaction costs to prevent war ought to be extremely high. That said, there are other significant practical difficulties to using suicidal diplomats. It might be superior to use trusted third parties (sometimes called the “Oracle of Delphi” strategy) to mediate conflicts, including handling sensitive information. (It’s also not clear how often asymmetric information with incentives to deceive is actually central to issues of war)

Extension of Why Are We All Cowards?

Adam Mastroianni argues society is experiencing a “decline of deviance” across all domains. Data shows people—especially teens—engage in less risky behavior (crime, drugs, teen pregnancy down dramatically since the 1990s), but also less creative/positive deviance (fewer people move away from home, culture has stagnated with sequels dominating, architecture and brands look identical, science makes fewer breakthroughs). His explanation: as life became safer, longer, and wealthier, people adopted “slow life history strategies”—they have more to lose, so they avoid all risks. The statistical value of life has increased faster than GDP. This shift began many decades ago, predating the internet. While declining crime is good, we’re also losing beneficial weirdness and need new institutions to preserve creative deviance.

My thoughts: While Adam did not frame his post as a direct response to mine (and I confirmed with him in conversation that he began his post before reading mine), I think his post can be reasonably read as an extension to my own rising premium of life post. In particular, he sets up a problem (the decline of deviance) that’s elegantly solved by the rising premium of life points I talked about (and he links). I still think there are real weaknesses to the “rising premium of life” explanatory model for all the diverse changes he and I have noticed, but overall it’s harder to come up with any theory (or small combination of theories) that have greater predictive value.

Highlights from Comments of Specific Posts

Bee Welfare

My first The Linchpin post, on bee welfare, written as a response to a previous Bentham’s Bulldog post against eating honey, received significant comments and pushback, particularly from the animal welfare, EA, and EA-adjacent audiences. The best comments are probably surfaced in the comments of my substack post itself, on the Effective Altruism forum, and to a lesser extent on X.

Lukas Gloor’s comment

The most interesting is probably from Lukas Gloor on the EA Forum, who offered a very extended response to the evolutionary model sketch I provided on both empirical and normative grounds:

For eusocial insects like bees in particular, evolution ought to incentivize them to have net positive lives as long as the hive is doing well overall.

There might be a way to salvage what you’re saying, but I think this stuff is tricky.

I don’t think there are objective facts about the net value/disvalue of experiences.[...]

While I find it plausible that eusocial insects suffer less in certain situations than other animals would (because their genes want them to readily sacrifice themselves for the queen), I think it’s not obvious how to generally link these evolutionary considerations with welfare assessments for the individual:

Most animals don’t have a concept of making changes to their daily routines to avoid low-grade suffering[...]

I concede that it is natural/parsimonious to assume that welfare is positive (insofar as that’s a thing) when the individual is doing well in terms of evolutionary fitness because happiness is a motivating factor. However, suffering is a motivating force too, and sometimes suffering is adaptive[...]

Maybe the reason some people succeed a lot in life is because they have an inner drive that subjectively feels like a lot of pressure and not all that much fun? I’m thinking of someone like Musk[...]

See the full response and exchange here.

Bentham’s Bulldog’s comments:

I also appreciated BB’s reply. He brings up wing-clipping of bee queens, which weakens my arguments about “Exit rights” some, but I think is overstated (since I think wing-clipping is not all that empirically common).

He also brought up a number of other points. Check out his comment for more!

Fixes

An earlier version of the post mistakenly said bees were r-selected. The actual discussion is complex (I currently think the r-/K- selection dichotomy doesn’t apply superwell to eusocial animals) but most biologists would consider bees to be K-selected. So I fixed the evolutionary section.

I also included the points about wing-clipping in the main text.

Other comments

Some people challenged my decision to only address the sign of bee welfare, and not the intensity or importance.

Some people challenged the idea that evolutionary just-so stories can tell us anything about animal welfare

(I see where they’re coming from, but I’m also very skeptical we have better options!)

While the comments were mostly positive, many people were generally critical for different reasons.

Overall reflection

It’s been slightly over four months since that post (my first substack post!), and with the benefit of hindsight and reflection, I think the comments didn’t update me that much! Right after publishing the post, I thought bees probably had net positive welfare with high uncertainty. Four months later, I continue to believe roughly the same thing.

The Rising Premium of Life

My second article, Why Are We All Cowards?, was very positively received by different corners of the internet. Besides Adam’s post citing it, the article was also the lead article for the July 12 subscription of The Browser, a newsletter aggregation service:

Linch | 10th July 2025

Wide-ranging discussion of risk. Interesting throughout. There is little doubt that humans are becoming more risk averse. The US’s value for a statistical life (now $11.4 million) has more than tripled since 1980, far outstripping life expectancy. Why do we prize safety more? Likely a combination of growing personal wealth, secularisation, smaller families, falling mortality rates, and psychological evolution

The article was pretty widely shared overall. I still see pingbacks to it from time to time in Korean or Spanish or something.

Universally loved?

I got some negative feedback on my choice of clickbaity title and overall framing, but surprisingly little negative feedback for the substantive sections, despite receiving >7,000 views.

The most interesting negative comment might be this r/slatestarcodex comment on how the article assumes a degree of rationality in people’s decision-making and risk-taking preferences, but I still stand by my overall position.

Overall reflection

I have a bunch of personal notes on why I could be wrong. Surprisingly, very few other people bring them up. Overall since writing the post, I’ve increased my credence in the phenomenon being real and under-studied!

Why Reality Has a Well-Known Math Bias

This post tries to answer a hard question that stumped mathematicians, physicists, and philosophers of science over the 20th century: why is our universe so amenable to mathematical description?

I provided an answer that I think is surprisingly elegant, relying primarily on anthropic reasoning that didn’t become prevalent until the late 20th and early 21st century.

So what are the objections?

BB’s comment

I’m not sure if he’s ever written it up, but Bentham’s Bulldog surprisingly had a pretty strong counter in conversation:

Anthropics explanations can explain effects, but they can’t explain away effects.

In other words, if your explanation is “we live in mathematical simple universes because mature minds can only exists in mathematically simple universes”, nothing is really explained away.

I think the objection is clever but I don’t find it that compelling. It sure seems like “I can only ever observe X effect, I can’t observe Not X” makes X much less surprising than if I didn’t believe that!

Or perhaps I didn’t fully understand his explanation! Still I think it’s the best counter to date.

Maybe I misunderstood Wigner’s Puzzle?

Over at r/slatestarcodex, u/ididnoteatyourcat claims I did not differentiate between algorithmically vs mathematically simple, and that’s a major missing part of the story.

I think you are misunderstanding a major part of what Wigner is gesturing at. Your explanation addresses why our universe is algorithmically simple, but not why it is so mathematically simple.

Have you ever tried to write a physics engine, say N-body Newtonian? What one finds rather remarkable, is how unsuited numerical algorithms are compared to an analytic description in terms of differential equations, as well as how easy it is to produce an identically simple algorithm which is not empirically adequate. You might also look at cellular automata for further intuition in that direction.

That is, if physics tells us anything, one of those things is surely that nature loves differential equations over and above algorithmic simplicity or even numeric tractability. There is something interesting and strange in that question that your analysis does not explain.

It’s intriguing but a) I’m suspicious he diagnosed it correctly, given that Wigner doesn’t really talk about algorithmic vs mathematical complexity in his original speech, b) none of the other mathematicians or philosophers I discussed my solution with brought up this point, and c) I suspect the empirical examples he gave for mathematical but not algorithmic/numerical simplicity were cherry-picked

Maybe Wigner’s puzzle wasn’t a real puzzle?

Some people, eg over at r/PhilosophyOfScience, think Wigner’s puzzle isn’t a real puzzle, and the universe only looks amenable to mathematical description because we are predisposed to thinking in this way.

I disagree. I mostly buy Hamming’s counterarguments, which I also briefly talked about in my original post.

Overall reflection

I still like my explanation, and think it’s vastly underrated in the discourse. But I think it’s more likely than not that I’m wrong for some deep reason I don’t fully understand. It also just seems so unlikely on priors that a question that eluded the best minds for so long can be solved so cleanly in one Substack post. It did help that I was using philosophical/analytical tools (anthropic reasoning) that weren’t really invented back when people were seriously pondering the question (and by the time the relevant tools were invented, the main thinkers either died or moved on), but even so, I probably am not so lucky!

Which Ways of Knowing Actually Work?

This one’s a doozy! Positive reception on my own substack comments, universally panned pretty much everywhere else.

Negative comments on specific tiers

Some people just disagreed with specific tiers on the tier list, and had Strong Opinions. See here, here and here.

Other negative comments

Many people just thought I was stupid, or didn’t appreciate the distinction I made between frameworks and the thing frameworks pointed towards.

Overall reflection

Really glad to see Etienne’s great reply to my post! If not for that I’d consider the post a failure as a practical matter, if not necessarily in terms of insight or correctness. I was also glad to see mostly positive comments and reception by people whose opinions on epistemology I respected, like Daniel Greco3.

That said, my negative experience with the reception made me somewhat more pessimistic about my own ability to communicate complex/nuanced/meta concepts. I gotta level up my writing and explaining skills more first!

Ted Chiang Review

My first breakout success! And it’s a book review lol. My review of Ted Chiang’s fiction got 30,000 views on Substack, the front page of Hacker News, over 700 karma on reddit, about a dozen in-person fans to show up to an event, and so forth4. Not too bad!

The comments were mostly positive, but given its popularity, I did receive several interesting negative ones.

Did I overstate Chiang’s uniqueness?

Isn’t that a basic premise of SF, to imagine a certain rule and how life would fit within that?

I’m not dissing Ted because I love his work as well but I’m confused by your assessment of what SF is.

As to his works, I think it’s very akin to Lovecraft

AceJohnny from HackerNews asks:

If you like stories of science fiction, I’m surprised no-one mentioned Greg Egan.

“Singleton”: what if many-worlds interpretation of quantum theory was real?

The Orthogonal trilogy, starting with “The Clockwork Rocket”: what if space-time was Riemannian rather than Lorentzian? Physics explained at https://www.gregegan.net/ORTHOGONAL/00/PM.html

u/punninglinguist claims:

I think you’re making it too complicated. Hard sci-fi is sci-fi that is about science.

That’s Ted Chiang to a T, even when he’s writing about counterfactuals.

Kimi (AI model) says:

Borges, Lem and Calvino also wrote “science whose laws differ.” A quick nod to these precursors would keep the praise from sounding ahistorical.

In general, many of my critics believe that either I misdiagnosed Chiang (and he’s obviously either hard science fiction or soft science fiction, rather than a third genre), or I acted as if his “third genre” science fiction is more unique than it actually is.

To the former, I disagree but ultimately words are made by man. To the latter, I say “fair cop” but it’s still rare enough to be worth emphasizing!

Other comments

I got hundreds of comments saying how my review is awesome, the best thing ever, etc. I totally agree with all of them! I’m a great book reviewer, and it’s about time my genius is recognized! But more seriously I’m glad to be in a community of fellow science fiction fans.

I also got into some tangential not very relevant conversations about AI, as well as an argument that imo was pretty bizarre about how I was supposedly “punching down other authors.” Ah well. Such is life.

Fixes

An earlier version of the review incorrectly said “In Exhalation, thermodynamics appear to work differently.” However, multiple commenters have kindly corrected me since. I regret the error!

Overall reflection

It’s good to be semi-famous! I hope more of my future articles become as or more popular. I don’t understand writers who don’t care at all about making money from writing or fame. Exploring interesting ideas is great and all, but overall I’d rather more people hear my ideas than less.

Part of me really wants to send my post to Ted Chiang and see what he says, but part of me is scared that he’d just turn our conversation into an irrelevant conversation about AI. It’s often safer to admire our heroes from afar!

Other posts

I have other posts I like, but either I didn’t receive that many comments, or the post is still fairly recent and it’s “too soon to tell” what the best comments will be.

I did especially like the response and feedback to my “reverse AMA” post. I was heartened by how intelligent, analytical, and accomplished many of my subscribers are! Broadly I think my readers, or at least commenters, over at The Linchpin are noticeably sharper than other online communities I’ve participated in or lurked at (eg LessWrong, ACX, etc). Which is nice though it’s unclear how long it’d last!

I also liked Corsaren’s comment on the Writing Styles post. I appreciated some of the discussion on r/GameTheory for the Puzzle of War post. I liked both the positive and negative testimonials for the board games strategy post. Finally, I enjoyed people’s attempts to tell other Intellectual Jokes to add to my Intellectual Jokes collection, even the bad ones.

Conclusion

In my first four months of serious blogging, I’ve so far received zero offers of sex, zero people willing to name their firstborns after my posts, zero $3.7 million-dollar checks, and any putative Middle East peace treaties seems tragically unrelated to my game theory blogging. But I got a few high-quality post responses, some detailed arguments in the replies, and hundreds of smart people taking my ideas seriously enough to argue with them. I suppose that’s good enough, for now.

In the next section, I used significant AI assistance to summarize others’ posts. I did not use AI assistance for my replies here or in other writing.

For this and future replies, I’m assuming readers have read the original posts referenced, and probably the replies as well. If this does not apply to you, I recommend either skimming/jumping ahead or clicking through and reading.

Though I partially respect him because he likes my posts. Epistemic circularity!

I believe my review is still on the front page of “ted chiang review” on Google search results for most people.

Thanks for the shoutout!

I actually never understood the idea that with the SIA, upon waking, SB learns new information.

However, I do tackle the SIA directly here:

https://ramblingafter.substack.com/p/highlights-from-the-comments-on-the

(You can skip to the "Refuting the Doomsday Argument section")

This one's even more subtle: There are many cases we can look at where the SIA makes perfect sense and holds mathematically. But I think some people try to over-generalize it. When asking anthropic questions, it seems extremely easy to make mistakes when setting up your assumptions - for instance, the orphanages examples.

(This won't make sense until you've read the post, but: There's the variation where one orphanage is known to be fake and the other real. There's another variation where one is known to have been all-boys and the other all-girls, and John is a male. I made the mistake in believing these variants are analogous, but they're not!! In an exchange with Joseph Rahi in the comments, I actually ended up arguing incorrectly against the SIA for a while.)

I think one intuition that may help is this: Observer selection effects are real, they're just a matter of treating observers like you would any other probabilistic object. As far as I'm aware, any example with conscious observers has an equivalent with objects. For example, swapping orphans to candy made the above difference between variants much more obvious. For another example, you could replace SB with a paper that says "I give Heads an X% chance". How do you decide how "correct" that paper was? How you count determines whether the Halver or Thirder strategy is better, and neither requires the idea of anything new being learned by the piece of paper after the experiment begins.

I got like 2k words into a blog post about whether or not “hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, etc…” based on our Twitter argument.

But unfortunately I don’t have a 30 day blogging residency to finish it… maybe after Manifest DC I’ll have the time to complete it 😭